The ideas here are inspired by Joshua Batson’s, “How to see a meromorphic one-form.”

- Introduction

- First idea: pushing forward

- Better idea: pulling back

- What can we do?

- Sample code

- Last thoughts

Introduction

Visualizing functions is hard work, especially when their source and target are not intervals in . In particular, students of calculus are faced with a real conundrum when we begin to think about, say, differentiable functions

or meromorphic functions

, because we don’t have enough dimensions to properly plot their graphs! A common workaround is to use phenomenological qualities, particularly color, to encode additional dimensions into our plots.

For example, given , the magnitude-phase technique takes advantage of polar coordinates. Taking the usual Cartesian coordinates

, this method colors the surface

in terms of the argument

mapped onto a hue wheel. This method is standard enough that it’s built into many mathematical programming languages! Mathematica can easily produce pictures like this:

ComplexPlot3D[(z^2 + 1)/(z^2 - 1), {z, -2 - 2 I, 2 + 2 I}]We can learn a lot from this picture—for example, we can see the roots (where the colors all come together) and poles (where the surface blasts off to infinity) of this function easily. We can put together more by swiveling the plot around, but we quickly run into lots of the well-documented problems regarding how humans make sense of area and perspective. By the way, be wary of pie charts—especially the 3D kind.

ComplexPlot3D[(-z^20 + 228 z^15 - 494 z^10 - 228 z^5 -

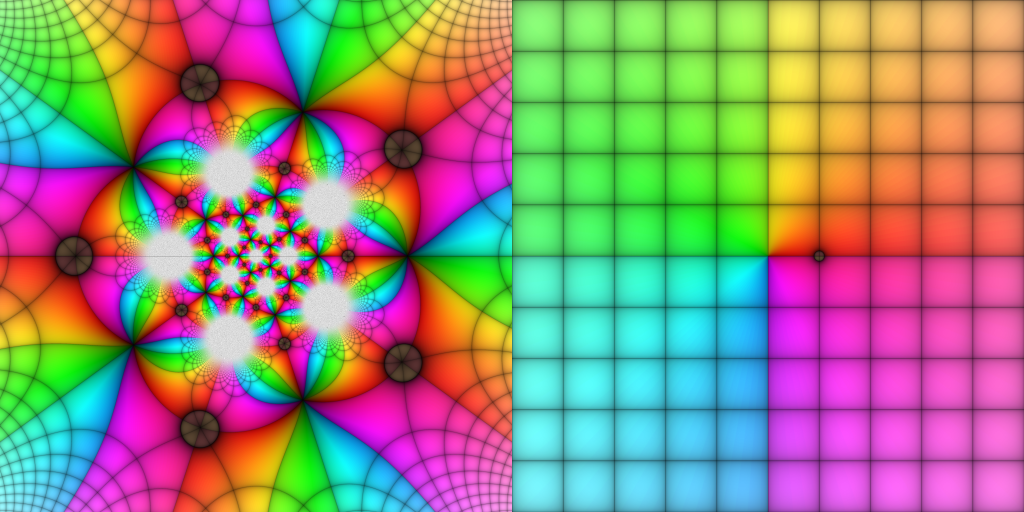

1)^3/(1728 z^5 (z^10 + 11 z^5 - 1)^5), {z, -3 - 3 I, 3 + 3 I}] Above is a plot of Klein’s icosahedral function , one of the mathematical objects that really sent me down this rabbit hole. Note that we sadly can understand very little about

from the image—the poles completely obscure its features!

While there are many other techniques for drawing functions of complex variables or maps between Euclidean spaces, I have seen very little on the really wonderful technique that Joshua describes in his paper. Domain coloring is the closest to what we will discuss here, which is very close to Mathematica’s ComplexPlot, but I think these still miss the mark when applied naively.

First idea: pushing forward

Functions are assignments—they go somewhere, sending points from a source to a target. So, when incorporating color into pictures of functions, it is natural to first think of pushing colors or other data along the function. This is a fantastic idea, but unfortunately it doesn’t work most of the time for visualizations. Let’s think about why with a quick aside (which can be easily skipped—in fact, this whole section can be bypassed if you want to just see cool math pictures already).

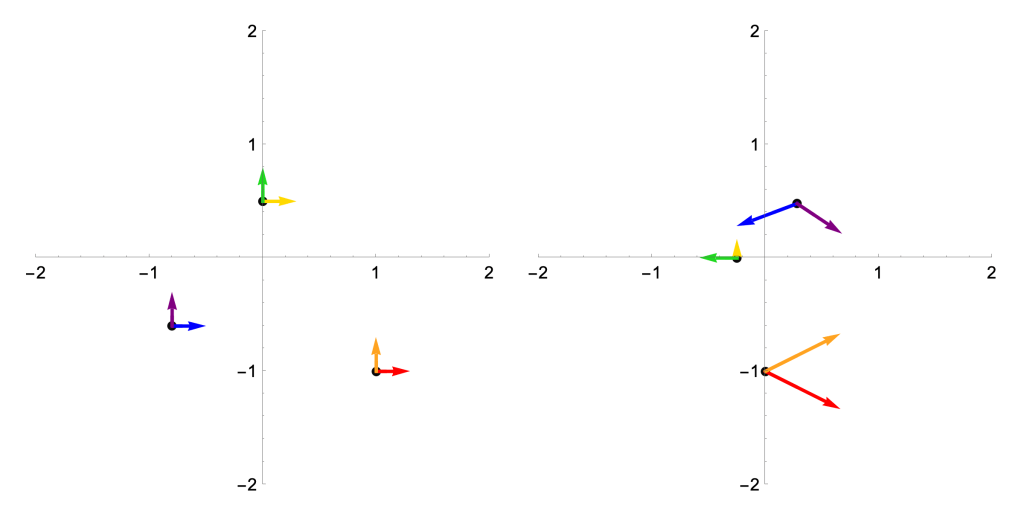

Pushing forward information is a great idea locally. This is a crucial idea in differential geometry. If we have a map, say , and a point

, then we can ask how $F$ varies along a tangent vector

by evaluating

This process is linear and defines a transformation with a strong geometric meaning: if we vary our inputs from

along

, the outputs will (to first order) vary from

along

. Moreover, if we write our vectors using the standard basis and

, then

is nothing but the Jacobian matrix

evaluated at . We can visualize all this using the pictures like the following.

While the picture on the left requires a nontrivial bit of computational power to render—those distortions are non-linear, so drawing the gridlines in the target take some work—we could sketch the one on the right with some pen and paper (and maybe a calculator, since I didn’t pick integer coordinates). That’s the power of calculus! For one last little treat, the determinant of the Jacobian at each of these points (which is zero if and only if the Jacobian is one-to-one, because linear algebra rules) tells us how area is being distorted by . Think about how we might see that in another such image:

In words: the columns of the Jacobian matrix at teach us what happens to the outputs as we vary along the corresponding coordinate axes. Whenever the Jacobian matrix is one-to-one (i.e., when it has a trivial kernel), we send little gridlines near

to little gridlines near

, perhaps with some non-linear distortions; otherwise, variances along some non-trivial vector go undetected and therefore

fails to be one-to-one near

. We are brushing up a very important idea in differential geometry: the Inverse Function Theorem.

Anyways, back to visualization. We might think “let’s use color to see what does by painting the source in an interesting way, then checking where each point goes and coloring them the same way.” That’s a fantastic idea, but unfortunately it’s doomed to fail for two important reasons:

- Not all functions are injective. If

are distinct points with

, then should we color

according to how we colored

or how we colored

?

- Not all functions are surjective. If

is not in the image of

, then what color should it be?

These are actually the same reasons why, while we can always push tangent vectors forward along differentiable maps as above, we cannot in general hope to push forward whole vector fields. The local does not always glue together into the global!

What a mess!

Better idea: pulling back

If we think carefully about what functions are, we realize that the previous idea has things backwards. It’s true, a map sends every

to a well-defined

, but if

isn’t one-to-one then we don’t always know how to color points in

. Instead, we should turn to fibers, which is a fundamental notion in mathematics (it’s crucial to every class I teach numbered 200 and above). Recall the idea of a fiber: given a map

and a point

, the fiber over

is the set of pre-images

For example, under the complex-valued function , the fiber over

it the set comprised of its two square roots:

. Note that every

has a (possibly empty) fiber over it. A good exercise which I assign to my students in Math 236 is to prove that the fibers of a map (if we omit

) partition the source

: every

belongs to one, and only one, fiber. This is exactly the sort of recipe we need for coloring every point in a unique way!

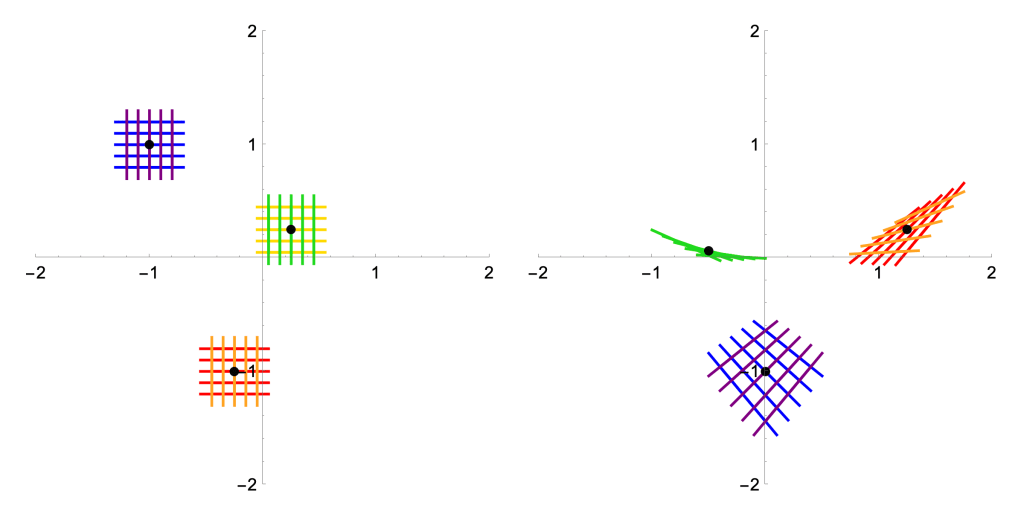

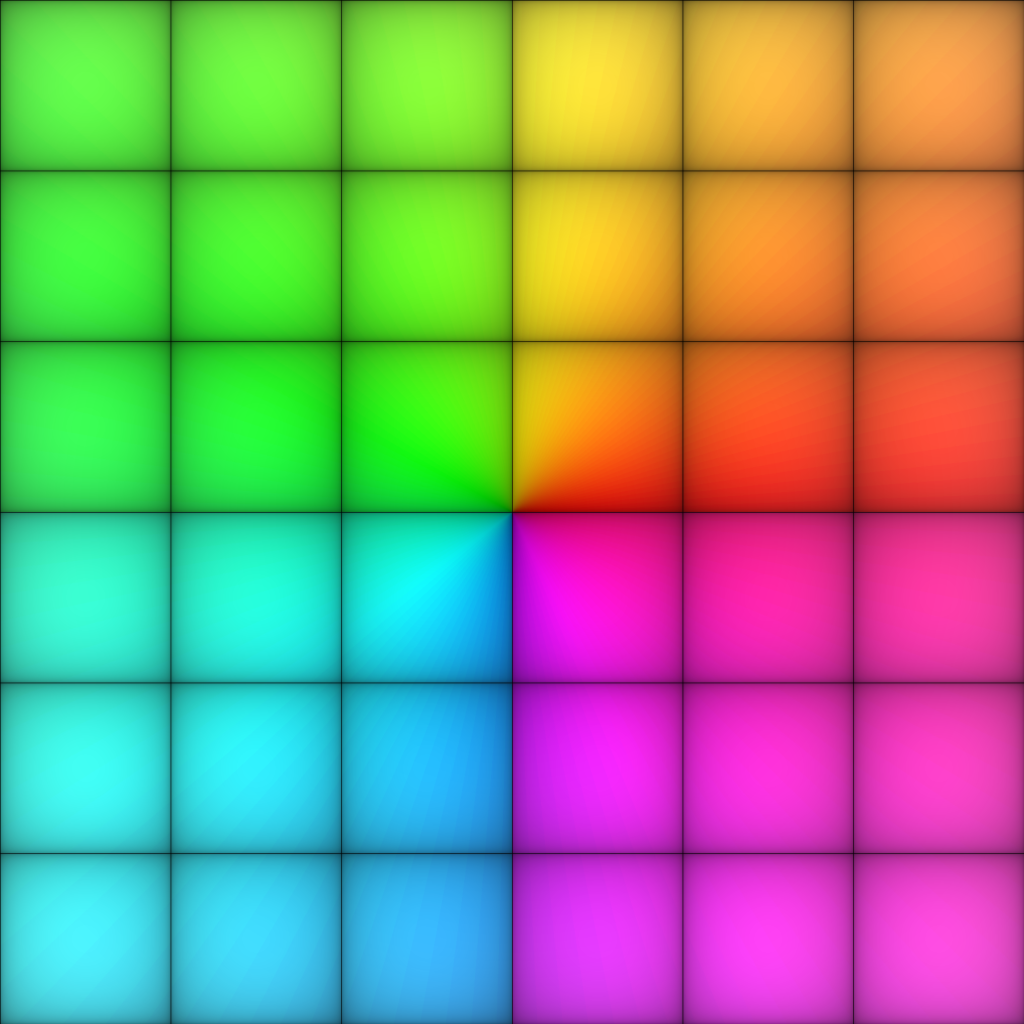

So we propose the following idea. Instead of coloring the source and trying to push colors along our functions, we color the target and pull back colors along fibers. This is best understood with some pictures which, after all, is the point:

Okay, fine, this isn’t the most illuminating example because it doesn’t look like anything is going on. But this is a picture of the function given by

… it’s not supposed to do anything! We are looking at the source and target using the same viewing window, where the bottom-left corners are

and the top-right corners are

. I have chosen a coloring of the target so that we can easily see the origin

, where all colors come together, and marked gridlines along the integer lattice. From there, I colored the source by checking where each point (say, over each pixel in the image) maps to under

, coloring

the same color as

. Okay, let’s do a slightly more interesting example so we can see things actually happen in a non-trivial way. How about

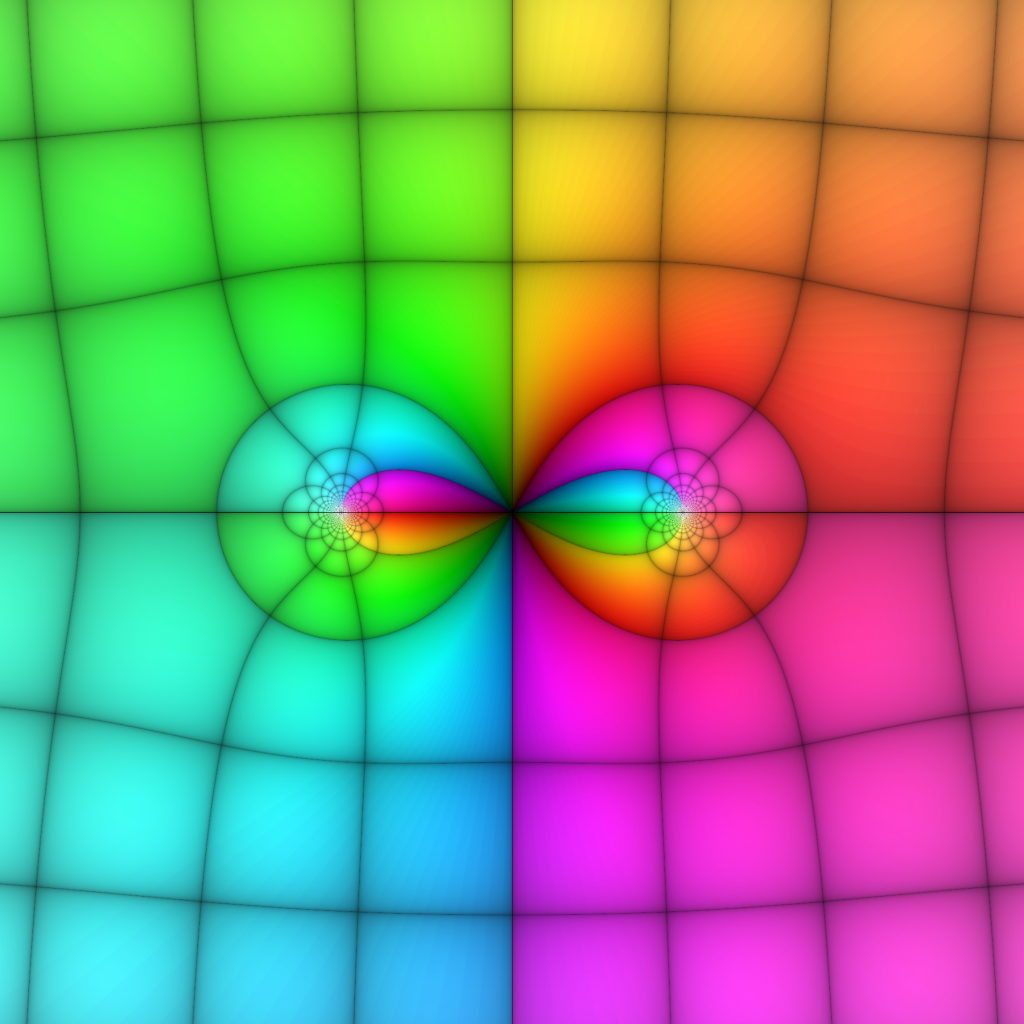

?

To keep things simple, I didn’t change the coloring of the target—more on that later. But, for now, big things have happened! Let’s look at some examples by listing some easy values of this function: and

. How can we see these in our picture? The value

is the easiest to check—in the target, that’s where all the colors come together. We can see that happen in two places in the source and, after some reflection, we realize that those are exactly the points

. On the other hand,

lies along the transition from blue to green, the closest such place along the origin crossed by a vertical gridline. Since this function is continuous, we can follow that logic by starting at either

or

in the source and walking along the blue-green transition until we run into crossings—and that takes us right to

. Something strange is going on, given how we have eight edges coming into

instead of just four like on usual grid paper, but more on that later. You can check other values, like

, using the same logic!

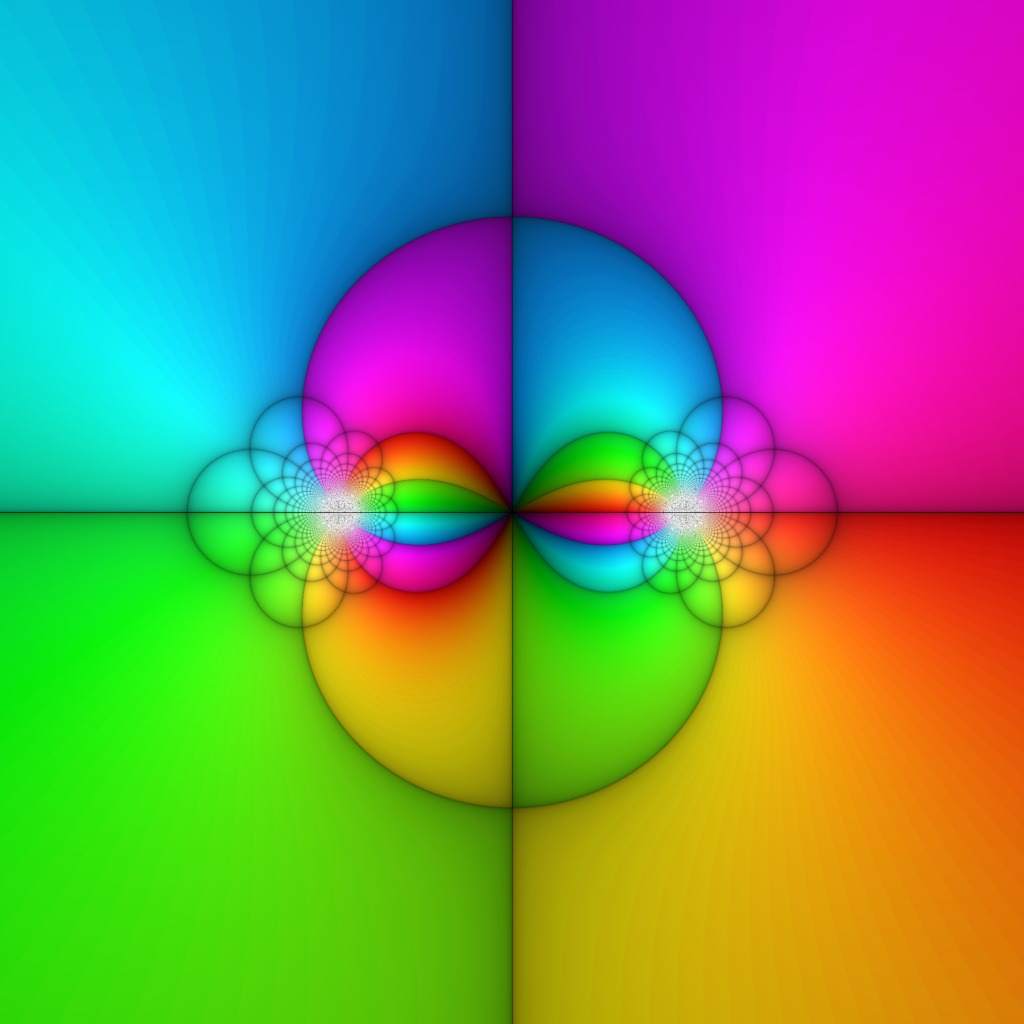

My main self-criticism with this method is that it’s hard to tell exactly where points are in the source, since we don’t label them. An easy modification would be to reserve some sort of color not used in the image, maybe a nice medium gray, to print and label a grid on the source. But I’m here for the aesthetics, so figure that out on your own! I’ll always plot the source and target using the same viewing window, so use that to gauge where things are for the time being. Okay, let’s try another polynomial function: .

Once again, we can see the roots of this function easily. More than that, and I invite the curious reader to reflect on why this is so—we can also see the multiplicities of the roots. In particular, the source coloring near looks, more or less, just like the target coloring at

. On the other hand, the source coloring near

does not look like the target at

; somehow, it seems to be doubly wrapped up! The picture is trying to tell us that

has a repeated root at

. For comparison, imagine a slightly deformed version of this function where I wiggle the double root apart into two nearby single roots:

I love these diagrams so much. You can see that if we zoomed in very close on those two nearby roots, they also would look (locally) like the target coloring at —because their multiplicity has dropped to

! What do you think a triple or

th root might look like, using this same coloring scheme for the target?

What can we do?

Here is where the pics get good

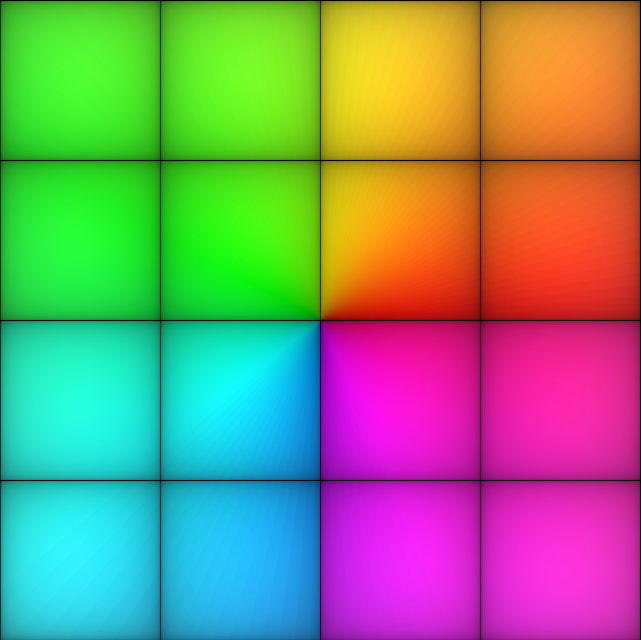

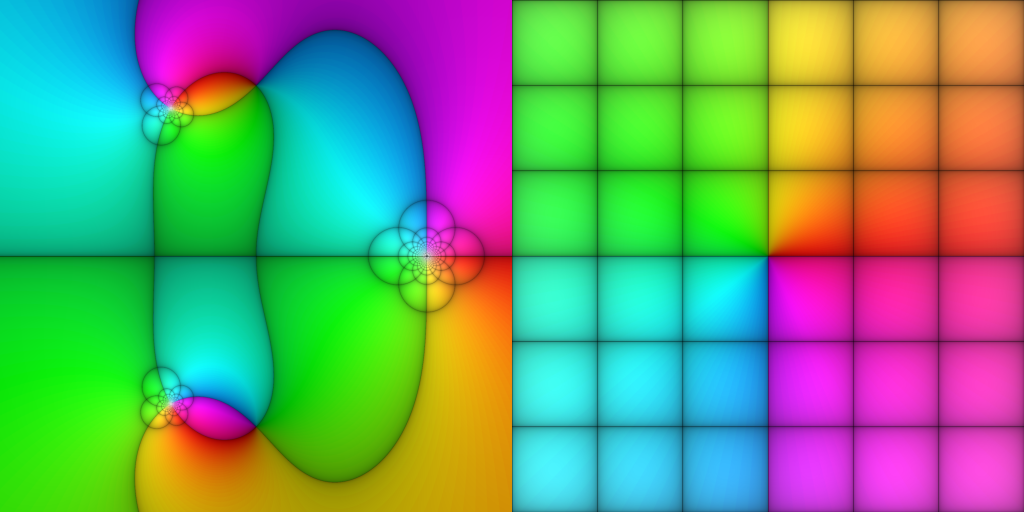

Taking stock, you might be unimpressed by all this. With the target coloring I introduced, we can easily recognize roots (and their multiplicities) for polynomial functions . But, if we look back at the images rendered at the start using

ComplexPlot3D (or just ComplexPlot, which look even more like what I’m producing above) in Mathematica, we realize that existing tools already accomplish that without all this work.

But we’re just getting started! First, let’s talk poles—a crucial feature of functions in complex analysis—which are hard to analyze in ComplexPlot3D because of how they zoom off the plot window. Let’s look at a few functions, with the same coloring as before, and see what’s what. Note that I’m printing all of these sources in the window from to

, so we don’t need to keep including the target plot.

Can you distinguishing the double root from the isolated root in the first image, or see the poles at ? What about the triple root in the second image at

? And the double poles in the last image? What about the asymptotic behavior of each function?—note that the first two images start to flatten out into the ordinary grid as we run out to the edges of the viewing window, since the associated functions are approximately equal to

for large inputs, while the last image shows us tending to zero like

as the inputs grow.

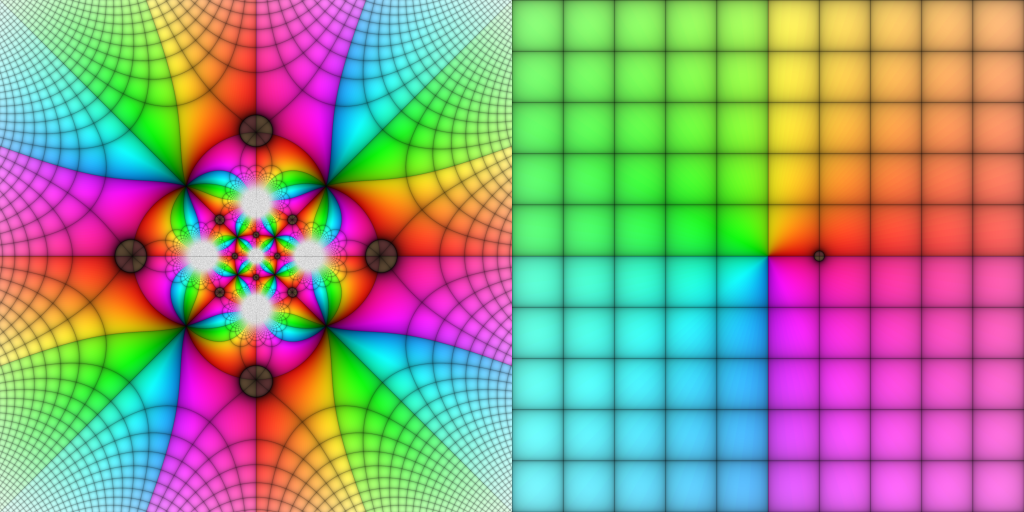

A quick note on this case of meromorphic functions—though, as we’ll see, many more things can be drawn with this method. As Joshua points out on page 4, due to the oft-celebrated fact that holomorphic functions are conformal (away from where their derivatives vanish), we need not plot both horizontal and vertical lines in the coordinate grid. My contribution to mathematical illustration is to say: “We need not, but we should!” Consider the following picture-proof:

Every once and a while, I need to sit with myself and reflect on how truly bonkers it is that we can have so much non-linearity and still preserve angles. Let’s lean into that! These pictures really illustrate a fundamental idea in complex analysis:

- Away from ramification points (where

), holomorphic functions can stretch, dilate, and rotate, but always conformally.

- Near ramification points, holomorphic functions look like

for some

.

- Near poles, meromorphic functions look like

for some

.

Now, I’m promising that our generalized perspective will grant us more. It’s time for the payoff. Until this point, we’ve used a coloring scheme on the target which allows us to easily see roots and poles of complex functions—when they take the value or

—among other things. But often we are interested in other, more specific values or behaviors! Well, why not mark them using our coloring scheme?

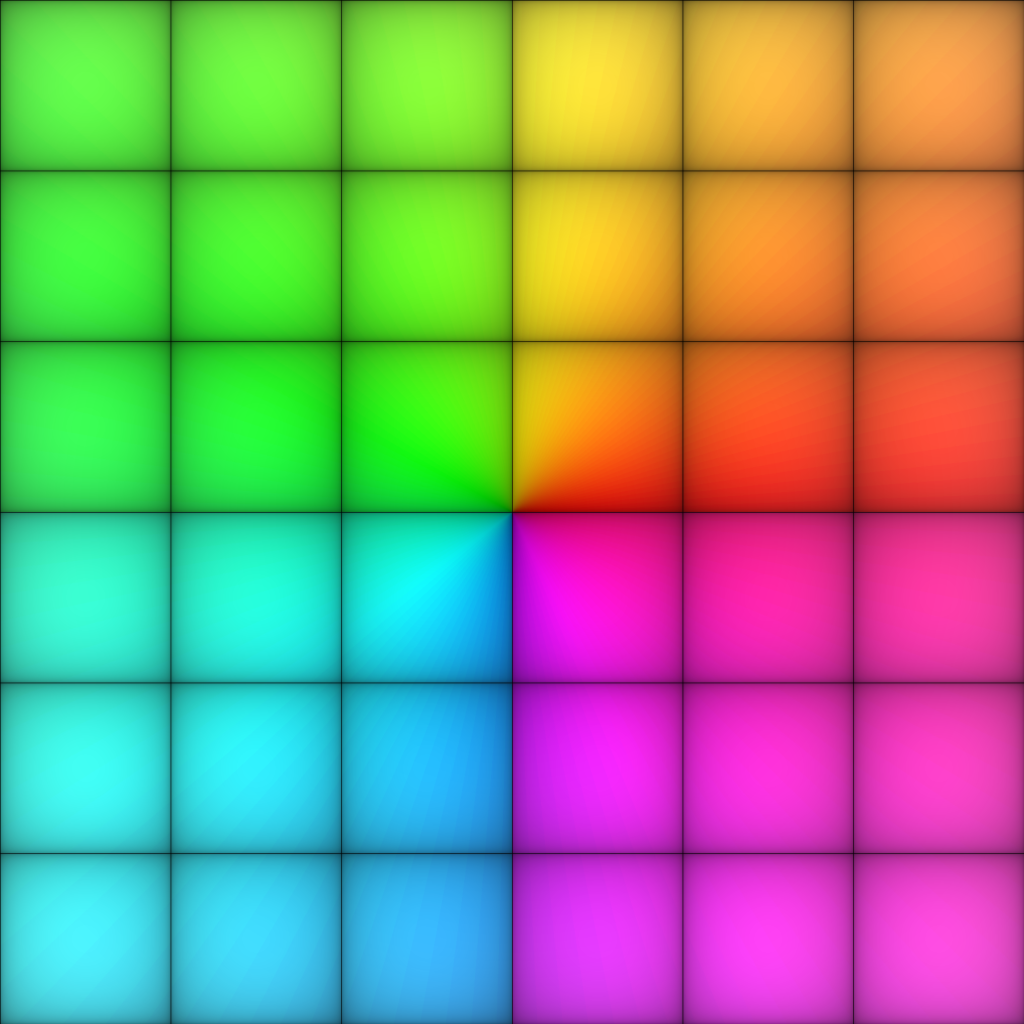

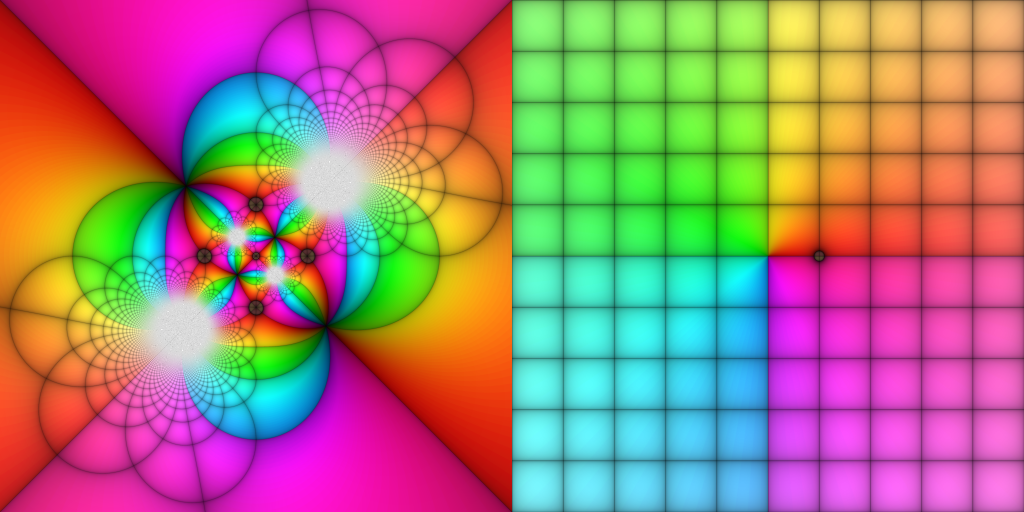

Klein’s icosahedral function

In a series of lectures published in 1888, Felix Klein outlined how one may use the symmetries of the icosahedron (that’s right, you nerds, a d20) to solve quintic polynomials. In particular, he used that the alternating group is isomorphic to the group of all rotations of an icosahedron, together with the notion of stereographic projection, to write down an action1 of

on the Riemann sphere

. This action is quite nice, being free except on three exceptional orbits that correspond to the set of vertices, edge midpoints, and face centers of the icosahedron—where it has stabilizers of orders

,

, and

, respectively. The idea is to encode these exceptional orbits as the roots of homogeneous polynomials which are invariant under the

-action, ultimately building a branched cover

of the sphere over itself that sends the icosahedral vertices to

, the edge midpoints to

, and the face centers to

. See more here and here.

All told, we have a rational complex function and we want to understand it with respect to its poles, its roots, and when it takes the value

(Is there a nice word for that? “Attains unity?”). To that end, I will decorate the target coloring with a small disk around

.

Remember that this whole story is really describing a branched covering of the sphere over itself, i.e., an covering of

less 62 points to

less 3 points. There is a corresponding picture for all the platonic solids (noting that the d20 and d12 are dual to one another, as are the d6 and d8):

Monodromy of algebraic functions

Oh but there are more colorings we might think about that can show us information about algebraic functions! In particular, these functions enjoy a beautiful property called monodromy that, among other things, obstruct how they can relate to one another and served as one of the fundamental phenomena that gave rise to algebraic topology. While it goes beyond the scope of this post to give a general framework for what’s going on, the fundamental idea is we want to understand how values of an algebraic function might vary as we traverse loops—taking square roots is a classic example, where we have to use branch cuts in complex analysis class in order to talk about √ as a well-defined function.

With the example of the icosahedral function, we want to understand what happens to loops about its branch points. In particular, we want to draw a little loop around and a little loop around

—let’s base the loops at

for concreteness— and think about what the lifts of these loops do to the fiber

. If all this jargon is a bit too much, you have several options: come back to this post after you’ve taken a bit of complex analysis or topology, come knock on my door or send me an email, or just enjoy the pics.

The first thing to notice is that the picture of the target is totally different. My goal is to understand these loops, not to otherwise keep track of the values of this function, and the coloring reflects that. Herein lies the real power of the pullback visualization technique: we can do whatever we want! For the experts, we can see that the loop about lifts to a permutation consisting of 20 disjoint

-cycles; the loop about

lifts to 30 distjoint

-cycles. Both of these permutations are even, which is good news, and even better news is that labeling them and punching the results into your favorite computer algebra system confirms that the monodromy group at hand is

.

Sample code

Here is a short bit of Python code for visualizing functions of a complex variable as described here. Note that the sample function here is defined using lambda notation and also that Python uses

** instead of the ^ operator for exponentiation.

from PIL import Image

from math import atan2, pi, exp, sin

# the desired function

f = lambda z: (z**2+1)/(z**3-1)

# set the viewing window and image size

(xMin,xMax) = (-2.5,2.5)

(yMin,yMax) = (-2.5,2.5)

dim = 480

# use to avoid 1/0 if f is rational

epsilon = 0.000001

# sample coloring procedure--experiment with your own!

def color_point(z):

(x,y) = (z.real,z.imag)

(r,theta) = (abs(z),atan2(y,x))

# color by quadrant using -pi < theta <= pi

if theta<-pi/2:

h = (2*theta/pi+2)/8+0.45

elif theta<0:

h = (2*theta/pi+1)/8+0.8

elif theta<pi/2:

h = (2*theta/pi)/6

else:

h = (2*theta/pi-1)/8+0.25

# have saturation taper off to infinity

# draw a grid along the integer lattice

# and scale everything into the 0-255 range

h = int(255*h)

s = int(255*exp(-r/10))

v = int(255*pow(abs(sin(pi*x)*sin(pi*y)),0.12))

# return as hue-saturation-value, will convert later

return (h,s,v)

pullback = Image.new('HSV',(2*dim,dim),'black')

pixels = pullback.load()

# walk through each pixel in the image

for i in range(dim):

for j in range(dim):

x = i * (xMax-xMin)/dim + xMin

y = ( dim-j ) * (yMax-yMin)/dim + yMin

# draw the source/target pixels simultaneously

pixels[i,j]=color_point(f(complex(x,y)+epsilon))

pixels[dim+i,j]=color_point(complex(x,y))

pullback = pullback.convert('RGBA')

pullback.save('output.png')

Now go have fun visualizing your favorite functions!

Last thoughts

I love how this technique vividly demonstrates the categorical process of pulling back (as in differential geometry, algebraic geometry, cohomology, etc). Given a function , we can think of a coloring of the target

as a map into a space of colors,

, where I’m perhaps being a bit vague as to what category of maps we are considering. With this setup, what we described above is actually called a pullback

. For the experts, this is a particularly visual example of a contravariant functor of points,

, where the map

is that induced by

. In this sense, we can apply the principles here to lots of maps

so long as the spaces involved can be effectively visualized (and colored).

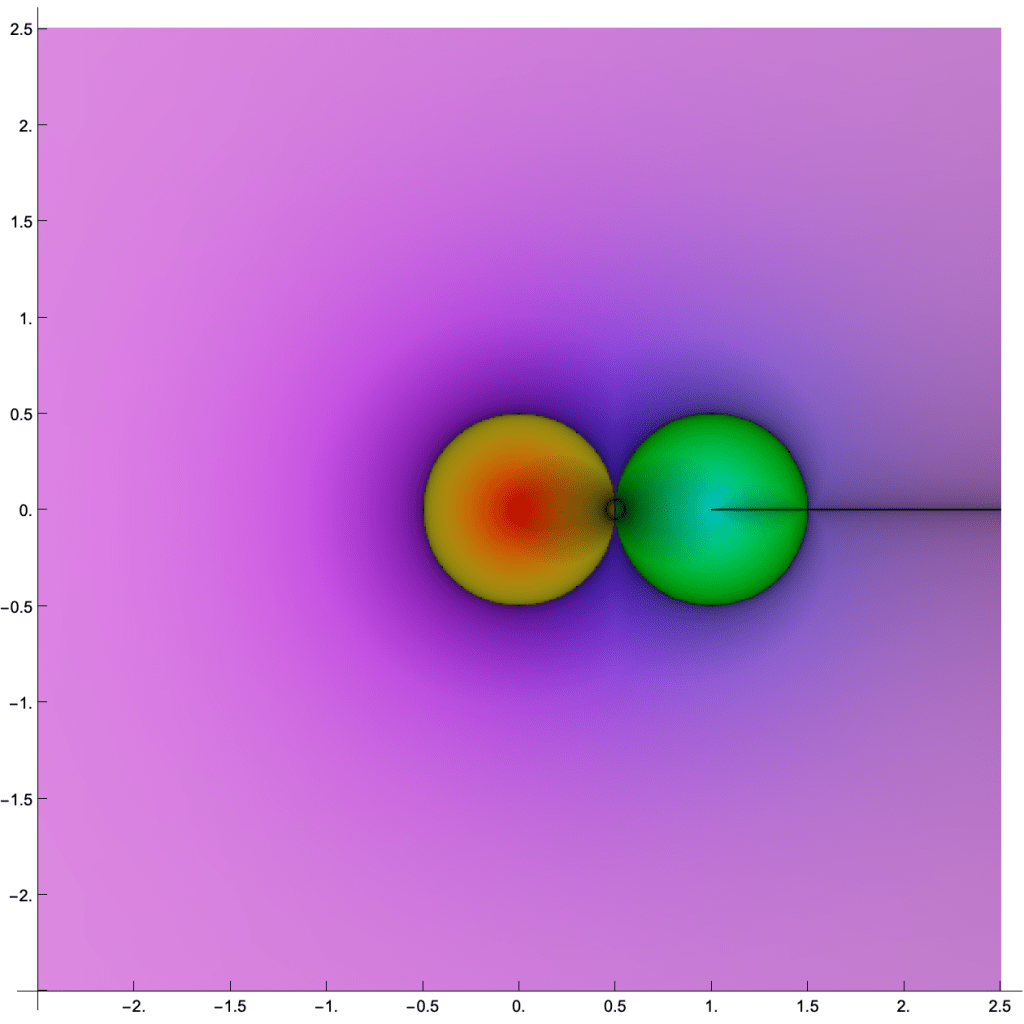

Here is a picture of Klein’s icosahedral function with a new coloring scheme on the target, but this time I’m embracing the fact that this function is a branched cover between spheres (which really allows the icosahedral inspiration to shine).

We conclude with (a movie of) a map . What can you say about it?

- For the experts, this is a projectivization of a 2-dimensional irreducible representation of

, the Schur cover of

. ↩︎